On December 6, 1535, one year after the founding of the colonial city then called San Francisco de Quito, three Franciscan Friars arrived to establish a foothold in the new city. Almost 500 years later, the modern day San Francisco Church and Monastery is home to an impressive collection of Spanish Colonial Art from the Quito School. The ancient buildings, the art collection, and the grounds themselves offer hours of enjoyment for tourists who enjoy history, art, and architecture.

The first church In Quito

Friars Jodoco Rique, Pedro Gocial and Alonso de Baena laid the cornerstone of the first Franciscan church in all of Ecuador on January 25, 1536. The simple adobe and reed structure, similar to the oldest church in Ecuador, was originally named the Conversion of San Pedro, in honor of that day’s religious feast.

Consecrated in 1605, the monastery was considered finished by the construction of its facade in 1618. Over the next decades, several other projects took place, including the legendary construction of the atrium, to result in the complex that we see today. Unfortunately, major earthquakes in 1755 and 1868 extensively damaged the church. In fact, at one time or another, the majority of the church has been rebuilt with the exception of the choir.

Visiting San Francisco Church

Visiting the San Francisco Church is as easy as walking through the front doors, which we have rarely seen closed. There is no entrance fee. Tourists are welcome to walk the aisleways, sit in the pews, and enjoy the daunting ambiance. You’ll notice as you read thru this article that we don’t have our normal number of photos. This is because photography in the church is very restricted. When we overcome this, we’ll update the article. So, for now, we only have photos of the nave, main altar, and choir.

Touring the monastery and the collection of religious art means entering through the museum entrance for a small fee.

The artistic and historical details below are all thanks to a Franciscan Friar, Benjamin Sanz, whose 1947 article in “The Americas” magazine provided source material for this article.

The Nave

The San Francisco Church is huge! In addition to the main nave or central room, there are two more on either side with chapels and altars of their own. Literally, every surface is gilded, painted or carved, creating an environment of impressive splendor. Larger than life-sized portraits of Franciscan saints and martyrs run along both sides of the nave. Perhaps the most impressive feature, the ceiling, is not original. A massive earthquake in 1755 brought down most of the original Moorish-style structure. During its reconstruction, the design of the ceiling was changed to today’s Baroque style.

The San Jose altar in the nave not only has an impressive selection of Baroque art, it also protects the tomb of Don Fransisco Inga, the son of the last Incan Emperor, Atahualpa. We have walked by this tomb dozens of times and never noticed this commemoration.

The two chapels on either side of the main altar, the Chapel of the Sacrament and the Chapel de Villacis, contain significant examples of paintings and sculpture from both European and Ecuadorian artists of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

There are so many objects of art in the nave and side chapels that we never tire of visiting the church. Each visit was a different experience as we noticed new items or new perspectives on art.

The Main Altar

The main altar is an impressive history of South American art in and of itself. The paintings, carvings, and statues that fill this end of the church illustrate the development of both native and European artisans since the sixteen century.

Starting from the outer walls, the paintings are of Franciscan martyrs and saints. These date from the original construction of the church as do the carved columns and figures which surround the paintings and altar. The majority of these artists are anonymous, as was common for the Quito School.

The works in the center of the altar are another story. The top retablo is The Baptism of Christ by Diego de Robles of Toledo, Spain. The work dates from the late 1600s and is one of the first works of this artist on the continent. He also was one of the first Europeans to establish a workshop in Quito.

Immediately below the retablo is a statue of the Virgin of the Apocalypse. Completed in 1734 by the best-known sculptor of the Quito school, Bernardo de Legarda, it is the inspiration for the iconic statue of the Virgin on top of the Panecillo and countless reproductions throughout the Ecuadorian and Colombian Andes.

Finally, directly behind the altar is another iconic Quiteño sculpture, the “Jesus del Gran Poder.” Since 1966, this seventeenth-century sculpture attributed to a Franciscan Friar and student of the Quito School named simply Carlos, has been the focus of Quito’s Good Friday parade, drawing tens of thousands to witness its movement thru the city on the shoulders of the faithful.

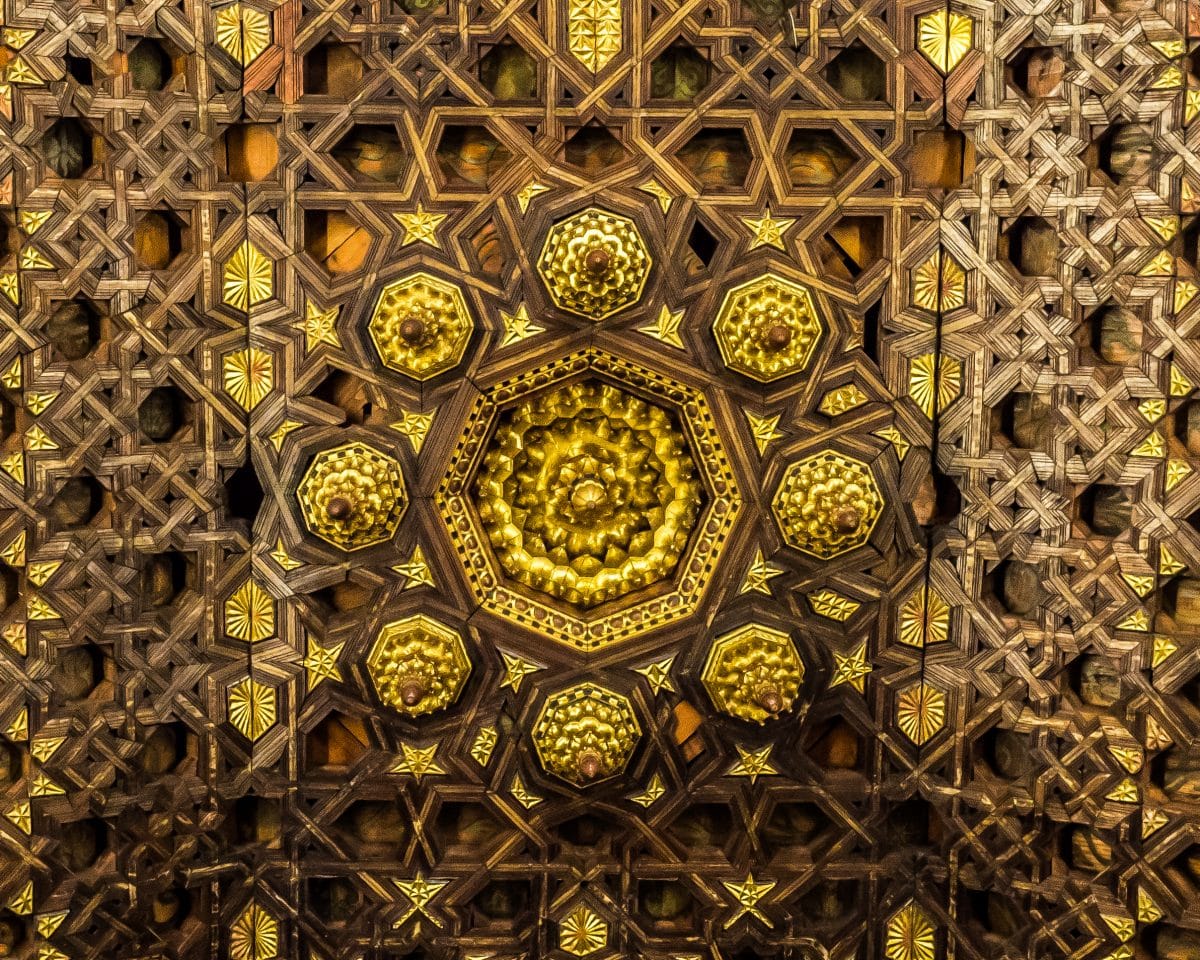

The Choir

The choir can be accessed for a small fee through the neighboring monastery and museum. It is the only part of the church where photographs are permitted.

The first thing that struck me about this space was the ceiling. A complex Moorish style in dark wood and gold leaf, it is nothing like the one over the remainder of the church. Intricately linked, all of these pieces are held together solely by gravity. There is not a single nail in the entire structure.

The ceiling in the remainder of the church is a result of the damage caused by the 1755 earthquake. This Baroque structure is constructed of plaster and gilt. Interesting, the entire project was completed by indigenous craftsmen trained at the Franciscan College of San Andres in Quito (founded in 1551), which was another of Friar Jodoco’s contributions to the city and the home of the famous Quito School of art.

The seats and decorations of the choir are carved from cedar, each a noteworthy work of art. The figure above each seat represents a Franciscan Saint or Martyr. If you look closely, the martyrs show the manner of their death. Each element is beautifully carved and painted in colors that maintain their brilliance to this day.

In the center of the room, a huge music stand holds court. It once held the large, hand-painted books of music used by the friars. Examples of these books can be seen in the neighboring museum.

The rest of the room is richly decorated with carved angels, geometric figures, and religious symbols.

Only part of the picture

The San Fransisco church is the arguably the best known part of Friar Jodoco’s work in Quito. However, it is only one part of his contribution to the history of Quito. He also founded the largest Friary in South America and the Continent’s first school for indigenous craftsmen. Both continue to have a major impact on the culture of Ecuador. We’ll take a look at them in my next post!

0 Comments