First published on December 16, 2017 • Last updated on May 28, 2019

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

In the southern province of Loja, the city of Saraguro, Ecuador is famous for its local traditions including the winter festival called Kapak Raymi. Officially recognized on the winter solstice, December 21st, celebrations and events crop up for weeks before and after.

Of course, calling it a winter festival is a little confusing. Saraguro is officially in the Southern Hemisphere, so Kapak Raymi takes place in the summertime. But when Ecuadorians refer to the seasons, it usually has more to do with the weather conditions rather than any date on the calendar. Some of you may remember reading about our trip into Cayambe National Park:

Although it is summertime in Quito, a mere 24 kilometers away, in Cayambe Coca NP June is winter time. Life on the equator is full of conundrums like this. And though we’d like to believe it’s winter because Cayambe-Coca is south of the Equator, Quito lies south as well. Seasons have less to do with actual location and more to do with weather conditions. If it’s raining most days, it must be winter.

So for the North Americans who read our blog or those who type search terms into the Google looking for things to do in Ecuador, winter festival is a definition that works… at least some of the time.

Our own introduction to Kapak Raymi took place one January in a small suburb outside of Quito where Saraguros living in or near the capital city celebrated a belated winter solstice. My friend Luz Vacacela, a well-known jewelry artist, promised a miniature version of the same festival that takes place each December in Saraguro. The day did not disappoint and we are more than ready to schedule our next trip to Saraguro to experience the larger, grander version of Kapak Raymi.

The Wikis

Our day began as we stepped out of our car and walked into the festival grounds. We were immediately met by the most colorful characters of the festival, the Wikis.

The Wikis met my camera with a pose that was very unexpected, their rear-ends. Luz, explained that wikis are the troublemakers of the festival. Their identities are hidden not only by their brightly-painted, hood-like masks but also by the high-pitched voices they use when speaking. They intentionally cause problems and often try to catch festival participants unaware. They liberally encourage the drinking of beer and chicha de jora, a fermented beverage made from corn.

Wikis bother everyone but seem to know exactly how far to take a joke. Perhaps this is why a wiki must be a member of standing in the community and earn his right to wear the costume, often by participating year after year in roles that lead up to becoming a wiki. We saw wikis toss children above their heads and gently tease older men and women in the crowd. They saved their worst antics for people their own age; young women were often met with sexually suggestive commentary, often whispered in their ears, and men were pressured to drink more beer. It seemed to me that a good wiki must know exactly how far to take a joke and to never offer an insult that a person wasn’t already willing to accept.

The Catholic Ceremony

After our introduction to the wikis, Luz directed us to join an audience waiting for the official start of the festivities. A large, white canopy stood on the edge of a tree-lined lot and a few rows of plastic chairs held Saraguros in traditional clothes. In the very front rows, several men and women wore the finest, dark black wool skirts, pants, and jackets, white shawls, and the iconic white wool hat with the under-brim painted in stark black-and-white geometric patterns. They were all members of the Saraguro governing council.

Others in the crowd wore other versions of the Saraguro traditional costume; the men wore short pants that we might call highwaters and most topped their white shirts with dark sweaters or ponchos. The women all had dark skirts and woolen shawls but were otherwise more brightly clothed with jewel-toned blouses and colorful, beaded necklaces. Many displayed large shawl pins of silver called tupus de plata; their design is circular, often incorporating symbolic elements like the Andean cross or the sun, with a precious stone in the center. A long chain attaches the shawl pin to the backs of traditional filigree earrings. Very few wore the heavy white hat but chose the more practical black wool hat.

The ceremony was a blend of speeches by council members and a religious service performed by a Catholic priest. A band provided provided music and the crowd sang along to drum and violin. A small troupe of young girls played a major part throughout, singing, dancing, and being called front and center by the priest. They were dressed in neon-blue wool skirts, brilliant hot pink shawls, bright white blouses and rainbow-striped, beaded collars. They were enamored with the small creche sat behind the main stage. Inside was not a typical nativity scene but rather several small figures of baby Jesus, one in a cradle and another dressed in full Saraguro traditional costume, including woven shoes.

The Procession

After the prayers, the assembled crowd stood up and reformed into a procession. The councilmembers took the lead, each person holding a small figure of the baby Jesus. They took us out to the dirt and cobble road and started walking. A full contingent of colorful characters followed along.

Several ajas, or devil-like creatures, danced along the route, weaving in and out of the procession. Their costumes are made with layers of flowing Spanish moss decked with a pair of deer antlers. A horde of young men dressed in bright red pants, white shirts, hot pink capes, and feathered head dresses attack the ajas as the procession makes it way along the road. A single bear (un oso) and a lion (un león) that looks like a leapord carry sticks and use them as weapons. They fought most with the little boys. Yet the people beneath the costumes were young boys themselves, only slightly older than the ones brandishing the hot pink capes. The wikis, of course, work the crowd, making trouble along the entire route. They picked up people and tossed them around. They sprayed party foam at unwary drivers who are suprised to find the small rural road blocked by an unscheduled procession. But in all their wildness, the wikis seemed a little like sheep-herding dogs, running here and there in a wild and crazy pattern that turns out to make a sense.

Amidst the craziness, an older man carried a burning bowl of incense hanging from a set of chains. The bowl holds palo santo and other fragrant wood and herbs that make a cleansing smoke as they burn. And all the while, the baby Jesuses move sedately forward. In Saraguro, the procession would end at the creche and the baby Jesuses would be placed with care in the church. But here, an unmarked spot in the road serves as a turning point and we about face and head back to the festival grounds.

The Quichua Ceremony

As you can already tell, Kapak Raymi of the Saraguro is a blend of Catholic and ancient Quichua traditions. While the procession blends the two, it also marked a divide in the activities for the day. Baby Jesus was returned to the creche and, while visited by many, he was not mentioned again. Catholicism faded into the background.

A shaman from Otavalo joined our party and led us in a ritual cleansing. He piped music from a Condor feather and blessed the mother earth with a splash of chicha before spraying a mouthful into the air in the direction of the audience. Off to the side, the ajas held a contest of gymnastic ability, taking turns somersaulting on a reed mat, their mossy hides flying through the air with the greatest of ease… perhaps greased by more than a little chicha of their own.

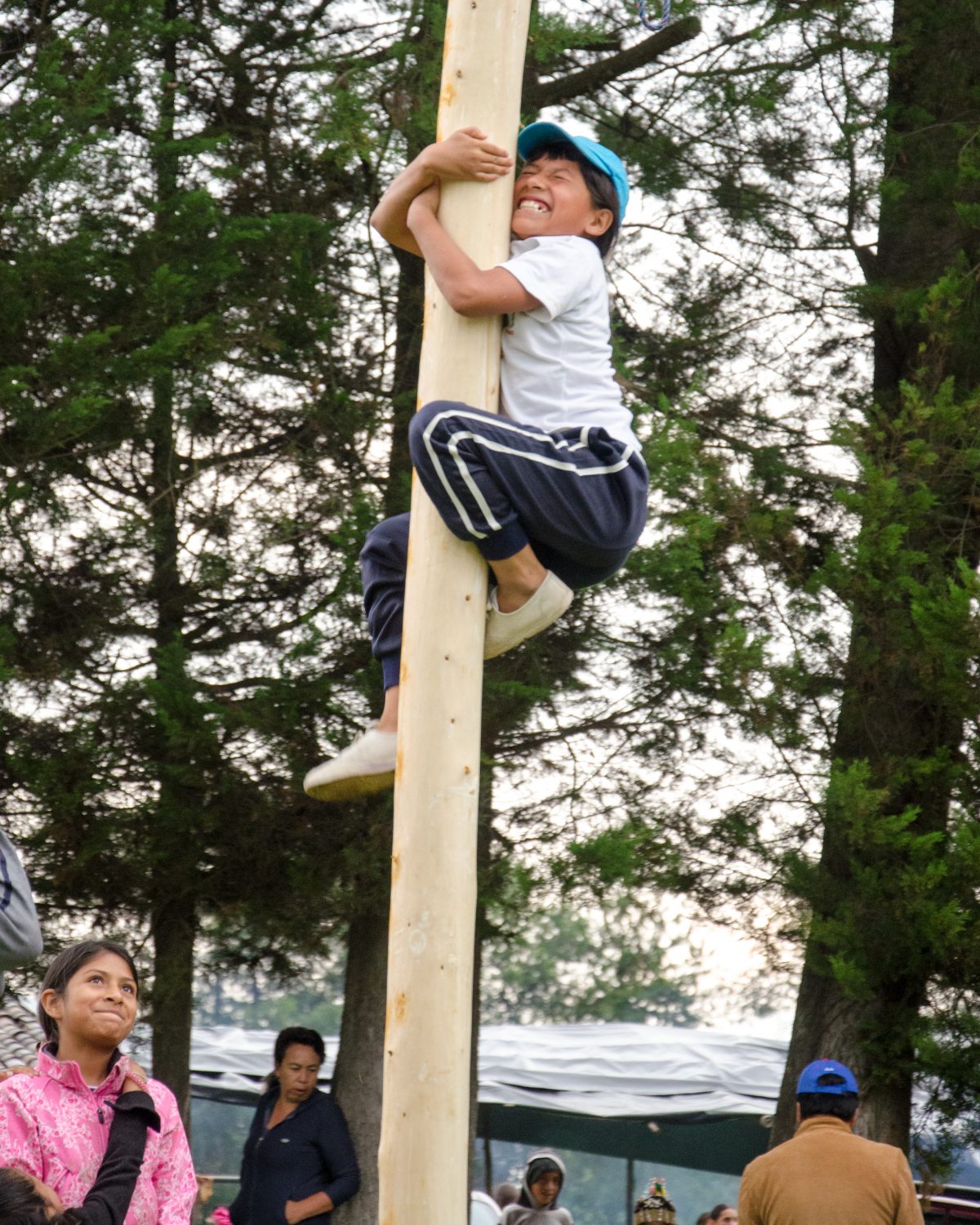

Then a group of men left with a purpose, as if a football game was about to start. Instead. they raised a huge log topped with a triangular shape, a little like a Christmas tree, covered with offerings of fruit and soda. It was an effort to lift the top high into the air, taking a step ladder, many hands, and a set of ropes to keep the top steady. The hole in which the pole was set was quickly filled and the log towered higher than any telephone pole. It swayed slightly in the breeze. Yet child after child attempted to climb it to reach the treasures up top. This was much better than football.

The Food

The raising of the food tree was a sign for the main meal of the day to arrive. We sat on the grass beneath the awning with Luz, her family, and the vast majority of Saraguros who came to enjoy the day. Meanwhile the council members took turns at a table set with chairs. First the women, and then the men.

Different families were responsible for different courses. Each family took pride in providing so much food that not only did no one go hungry, but everyone took home leftovers. Luz told me that it was a very poor festival indeed if leftovers weren’t part of the final equation. We ate mote (hominy) with fried pork, ears of field corn boiled until each fat kernal popped off into our fingers, and bowls of chicken soup thick with potato, and yucca. Little did we know that families bring their own bowls and utensils but people were kind and offered their own. We ate in shifts, as dishes were washed and brought back into service. When we couldn’t eat fast enough, Luz brought out plastic bags for our leftovers. There was physically no way to eat everything we were offered.

And then came dessert: freshly baked bread, blocks of young farm cheese, and rivers of miel de panela, a sweet syrup made from cane sugar spiced with cinnamon and cloves. We dipped the bread in the sweet syrup and ate it by the handfuls. Sticky fingers tore away pieces of salty cheese before heading back for more bread to dip. Women arrived with huge vats of panela to refill bowls and many a child probably had stomach aches later in the day.

The Theater of Kapak Raymi

The formerly cloudy day had given away to blue sky, as often happens in the Ecuadorian Andes. We took our full selves and moved into the late afternoon sunshine. The large open grassy area gave way to an informal stage and we were in for an unbelievable show. First, the young girls in their colorful outfits danced to traditional music, waving handkerchiefs to the onlookers. One little girl, barely a toddler and not yet ready for the responsiblities of being in the troupe, took to the field. Maybe she wanted to copy her older sister. Maybe she just wanted to dance. Either way, she captured everyones’ hearts as she swayed in her traditional dark skirt and salmon-pink silky blouse.

Then came the young boys, dressed all in black with sharp beaked masks on their heads, flying and fighting on the stage as real condors might do in the air. The wikis were next. They reminded me of court jesters, out to make the crowd laugh. They fought and wrestled. They played tug-of-war. Their colorful costumes shone in the late afternoon light.

The bear and the lion came out to joust. They paraded around, attempting to one-up each other with machismo-like bravado, stroking their man-parts to show the crowd what they were made of. They paroled the edges of the audience and when I tried to snap a photo, the lion offered a rather crude exchange of favors, a photo for fellacio. Shocked, I looked at my friend Luz who was laughing so hard that she could barely explain that this was normal behavior for the lion and something that I should have expected to happen. Culture shock comes when you least expect it.

After the show, families lounged on the field, soaking up the last rays of sun. It was almost like after a Thanksgiving meal but no one was snoring. Children ran around playing. Men hung together, sipping on large brown bottles of Pilsner beer. Women sat together, talking with friends and family that they may only see a couple of times a year. There was a good feeling in the air. It was time for us to leave, on a high note, before the sun actually set. We left, thanking Luz and her family many times over. Our day had been replete and to stay for any more would surely be too much of a good thing.

Was this Kapak Raymi or Navidad?

Hi Louise, this was a Kapak Raymi event celebrated in January in Quito, Ecuador. In general, Kapak Raymi is celebrated in the days around the December Solstice, December 21st. For that reason, it is also considered a celebration of Navidad. When in Saraguro around this time, there are events taking place daily, including on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day. If you would be interested in visiting, I suggest reaching out to Lauro at Saraurko.com. His team can help arrange for a homestay and/or community experiences with local families. I met him while touring Saraguro and today, I manage their new website.

What a detailed description of your experience! Thank you for capturing it so vividly.

Thanks so much for your kind words, Melissa. I hope you also get to experience Kapak Raymi with the Saraguros one day.