First published on January 18, 2019 • Last updated on February 7, 2022

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Among Ecuadorians, the Tulcan Cemetery in Northern Ecuador is famous for its evergreen statuary, huge topiaries carved from living cypress trees. The history behind these natural monuments begins almost 90 years ago.

Tulcan Cemetery Lives Up To The Hype

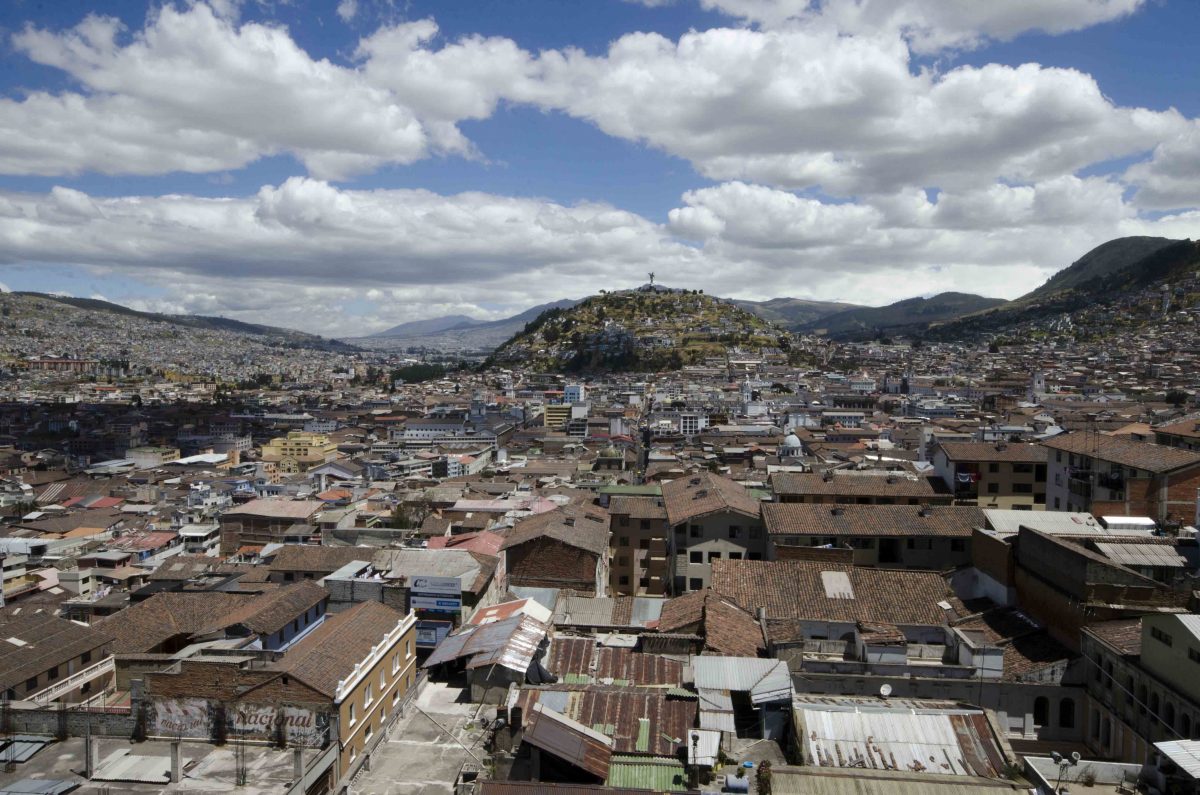

The first thing you notice when you walk onto the Tulcan cemetery grounds is that the topiaries of this place are big. Real big. Like over 12-feet tall, stretching for at least 200 feet to either side of the entrance (and that was only the front part of the cemetery). I could tell right away that this place would live up to the hype.

Where It All Began – God’s Altar

Walking around the oldest section of the topiary garden, called God’s Altar, I was amazed at the farsightedness of Jose Franco, the creator of these works, was when he conceived this project in 1932. He was the Tulcan Municipal Park Director when the city dedicated the new cemetery. He noticed that the soil on the 20-acre site had high levels of chalk which made it perfect for growing cypress trees. He began to plant cypress in 1936 and, as they grew, carved figures out of their foliage and branches. The rest, as they say, is history.

The figures in God’s Altar run the gamut from animals to religious figures to Incan statues. Strolling the grounds, it was easy to lose contact with the rest of the cemetery due to the dense foliage. I felt like Alice in Wonderland entering a new and bizarre world and wondered if the Red Queen or the White Rabbit was going to jump out from the hedge.

And the Topiaries Spread – Memorial Park

In 1987, Tulcan-native Lucio Reina started work in the second section of the topiary, called the Memorial Park. The best view of Memorial Park is from the top of the huge burial niches that surround the garden on three sides. While climbing on top of these structures seemed really odd to me, it is a common practice and no one batted an eye. In fact, families were on top of all the structures taking souvenir photos of themselves with the Tulcan cemetery in the background.

The style of Memorial Park is quite a bit different than the older God’s Altar. Rather than having the topiary figures close together creating a maze-like area, the park is organized into multiple sections surrounded by topiary hedges. This arrangement allows for the cemetery to use the enclosed land for burials much more effectively than the original garden.

Fortunately, this newer style does not detract at all from the experience. There are arches, statues, and a wide variety of topiary cut into the tops of the hedges dividing the area into distinct sections. A number of stand-alone topiary figures on the outskirts of the park are well worth seeking out.

Still under construction

The Eastside of the cemetery also has the beginnings of topiary art. Planted about 10 years ago, the young cypress trees are just beginning to mature enough to begin the slow process of transformation from hedges into figures. Even without many carved trees, this section is worth a visit to see the carved arches and the towers of cypress that will become the statues of the future.

Tulcan Cemetary Designated A Cultural Heritage Site

In recognition of the outstanding work overseen by Jose Franco, the cemetery was designated a Cultural Heritage and Nature Tourism site by the Ecuadorian government in 1984. The cemetery was renamed the “Jose María Azael Franco Guerrero” Municipal Cemetery in 2005.

After nearly 85 years, the Tulcan cemetery, with its 300 plus topiary figures, is a singular destination for visitors to the region. Jose Franco’s topiary legacy fully delivers on his desire to create a place “so beautiful that it invites one to die.”