First published on January 7, 2015 • Last updated on February 7, 2018

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

I have never planned a trip over Christmas before. We’ve always spent the holiday either at home or with extended family. We usually have a Christmas tree, except when military moves make it complicated and we don’t. We begin the day with biscuits and sausage gravy, a tradition from my husband’s family. Now that the boys are older, we open presents after breakfast. We usually end up outside for a walk and we eat a special dinner that never uses the same menu twice. In between all this, we play games like Cribbage or Hearts or Oh Hell! or work on a puzzle or read a new book and just enjoy spending a low key day together.

Christmas Day while traveling in Peru was nothing like that at all. The main festivities in Puno took place Christmas Eve with Mass at the local cathedral and fireworks into the wee hours of the morning. Instead of celebrating with the locals, one of us slept off altitude sickness, and the rest were content to be in a real bed and not have to get up before the crack of dawn the next morning.

When we woke, none of us had presents to open. Our present to the boys was the trip itself. And presents from family were waiting back at home until New Year’s Eve. I wouldn’t be cooking anything, much less sausage gravy! Instead, we started the day with a European breakfast of yogurt and fruit, slices of sweet bread, great South American coffee and hot chocolate for the boys.

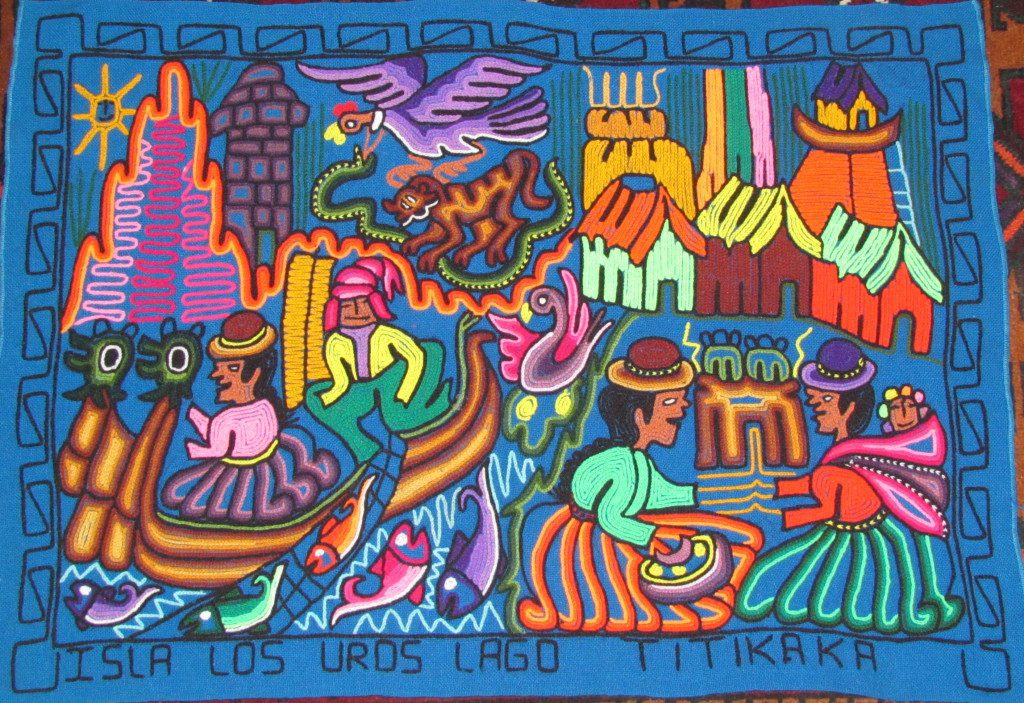

No, our Christmas wouldn’t be spent playing cards or reading books. Instead, we would spend it out and about, touring two local attractions on the Peruvian side of Lake Titicaca, the man-made Floating Islands of the Uros and Taquile Island, famous for handwoven textiles and clothing. Sounds like a great day, right?

After breakfast, we met our guide in the hotel lobby and proceeded to pick up other tourists from different hotels in Puno. When we finally boarded our boat, the weather was cold, wet, and very damp, the kind of damp that sinks into your bones. The small boat was packed, not one seat empty and very little space to move around. The driver sat in the very front and peered out the front window. My family sat in the very back and occasionally took turns sitting on a hump that covered the engine. The warmth of the engine worked its way up through the makeshift seat making it the best seat in the cramped cabin, as long as you didn’t mind missing a backrest.

Our guide used a microphone to speak to us. You would have thought in a cabin so small that his voice would have been heard by all but he had to contend with the noise of the engine, which wasn’t quiet. And he started to fill us in on what to expect for the rest of the day.

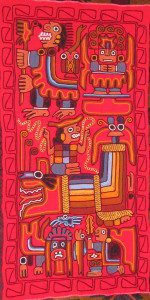

Our first stop was a short distance from shore, the Floating Islands of the Uros. Although the artificial floating islands have a long history, the current residents have been brought by the Peruvian government from the mainland to provide a historical and cultural tourist destination. Most do not live there year round. They may have ties to the pre-Incan Uros and they may not. Like many tribes in the United States, native South Americans found their families and cultures tore apart by Europeans wanting to educate the masses. Much of the re-education took place in the early 20th century and clear connections have been lost. What is clear is that modern Uros build the islands in the same manner, they live in the same type of structures while there, and they follow many of the same traditions, like fishing and building boats from reeds. The modern Uros, however, also send their kids to school on the mainland, via motorboat, many have solar panels to bring electricity into their communities, and they earn money through government subsidy and by selling their artwork. The men fashion miniature boats and mobiles out of native grasses and reeds while the women embellish brightly colored fabric with starkly contrasting thread to bring in very needed hard currency.

We were traveling in the off-season and it was very clear from the closed down islands that many, many families live on the mainland and only live on the islands when the tourist business demands it. Obviously, the demand must be great because we passed island after island, reed boat after reed boat, before reaching our destination, a floating island with about half a dozen huts and maybe two to three families. We tourists sat down on reeds that had been bundled into benches, sort of like sitting on well-packed hay bales. Not warm on a cold day and I couldn’t imagine how the families living here stayed warm on a day like this. The Uros consider themselves black-blooded and impervious to the cold. While trying to focus on our hosts rather than on the biting cold wind, we learned the process of building a floating island, beginning with the peat-like blocks of soil that allowed the island to float, then to the reeds that covered the blocks, and on to the anchor that kept the island from floating away. Add a pointed hut for the ancestors, a small attached island for the kitchen, and a few simple huts for homes and there you have it, a floating island. We were shown the fishing holes that are cut into the reed layer with a huge machete like knife. Much easier than the drill of an ice-fisherman though the final product was very much the same – a hole into which the fishing line and lure went.

|

|

|

|

Next we were invited into their homes. Our group was large so they divided us into family sized units and each group followed a woman to her home. I was separated from my own husband and boys but followed my guide into a small hut that was dark and warm, very cozy compared to the wet outside. Our hostess lit a small lamp, and sat down on the edge of a bed big enough for two covered in warm wool blankets. She motioned for us to sit on the small bench of reeds to the side. Then she introduced herself as Candelaria and told us a little about herself and her family. Her days are spent cooking and sewing. Her own children were about the same ages as my own, 13 and 15, and were both boys as well. The children of the Uros move out of their parents’ hut to sleep with the other children when they are old enough so this small space where we were sitting seemed manageable for two until I realized that this was it. The living room, the kitchen, all of that existed outside, in the elements.

The tourists who came in with me were from Canada, a husband and wife and their two sons. As I was able to speak Spanish and they were not, I became the translator of the moment. I found myself torn between wanting to ask more questions about living on the islands and trying to help this woman sell her and her husband’s handiwork. The hand-embroidered pieces she showed us told the story of the Uros arrival to the Islands to the modern day. I was embarrassed by the Canadian husband who insisted on offering such a low price to this woman for her hard work. I have sewn by hand and by machine; I knit and I quilt; the time spent in hand arts can never truly be recovered in money but the amount charged should at least cover the costs of supplies and enough profit to make the enterprise worth repeating. This man offered not even enough to cover the cost of materials. His wife looked embarrassed. The woman selling to us shook her head at his offer. I don’t even remember if a counter offer was made. It was clear that he wasn’t buying unless he could make a bargain that was paramount to stealing. The irony was that you could tell he had money, much more money than my family. They were all dressed in the latest outdoor gear in brand names that come dear. And I wanted more than anything to make it clear that this man and his family were not all that North America represents – you see, in South America, Canadians and Americans (they call us Estadounidenses because those from South America are also Americanos) might as well be from the same country. But my quest was pretty damn hopeless because the people that can afford to travel around South America probably are more like these folks than like our own family. We’re the odd ones out, a military family that can travel in Peru because we were already more than halfway there thanks to my husband’s assignment. In the eyes of the people of Peru, we are rich but compared to these Canadians, not so much. Is it money that makes them indifferent? Or just that trips like the one we were one introduced them to the culture of a people in a shallow way so that it was easy to miss the beauty or appreciate a different style of living?

We left the island soon after that, my own treasured hand-embroidered stories safely stowed in the backpack. We jumped back on the boat, found our seats and slowly started to warm up. The boat started to rock more and more as we went further away from shore. My youngest son was looking green around the gills… his altitude sickness was not gone after all. We were all feeling a little sea sick, a small boat rocking in the windblown water, the temperatures cold and damp but the boat itself overly warm at times. And this small engine roaring loudly in our ears propelled the boat ever so slowly across the lake. We were looking at a long day ahead of us.

It seemed like hours later when we arrived at Taquile Island. We should have been excited because we were going to walk the island and stretch our legs. Unfortunately, the rain had picked up steam and was coming down in a solid drizzle. It felt like the worse day of the Inca Trail all over again. The cameras came out for an occasional rain-spotted shot of the landscape but for the most part, we focused on getting there, not on enjoying the trip itself. We passed farm houses and terraced farm land, all empty of people and animals other than a few goats we saw very close to the town. We strode under ancient stone archways with capstone heads watching us as we passed by and trudged up steps slick with water. The hike took us about 45 minutes and the drizzle never stopped. A town plaza had never looked so inviting!

Everyone was inside, either in the church or the small shop where the local artisans had their items for sale, each tagged with name and price. There would be no dickering here. UNESCO has declared this island a heritage site and the local people understand the worth of their work. And the work was truly art – we could buy clothing and blankets woven on handlooms by the women or knitted hats and scarves made by the men. My husband was thrilled to purchase a traditional man’s hat from the very man who had made it, dressed in traditional garb and proud of his work. It was difficult to talk to anyone as they spoke Quechua, not Spanish, but I hope that it was clear from the smiles on our faces that we very much admired all their work. I can see why UNESCO wants to help preserve this way of life.

We had a few minutes in between shopping and lunch so we popped into the small church next door. The service had yet to begin and the locals where all a buzz greeting one another. They didn’t seem to mind when we sat down in a back pew. Almost all were dressed in local costume, dark pants or skirts, white blouses and very brightly woven waist bands and caps. Everyone was exchanging coca leaves from small bags hanging from their belts. I still wonder if this was because it was Christmas Day or if this was a standard greeting on other days of the year. We did learn later that the waist bands worn by married men are woven by their wives and gifted to them upon their marriage day.

By the time we sat down for lunch, we were starved and thankful for a warm place to sit for a while. On the island, families take turns being the restaurant that feeds the hordes. The older women worked in a small, warm kitchen, the younger daughter, a teenager served us upstairs and offered us a choice of two meals – fish or tortilla de papas and the father welcomed us and helped out where needed. The youngest boy I caught hanging out in the kitchen near the food – of course, don’t young boys always hang out where they are most likely to grab a meal? We started with a bowl of quinoa soup and each main was served with rice and potatoes. This was standard in both Peru and Bolivia and we still marvel at eating quinoa, rice, and potatoes all at one meal!

It was only then, after we had eaten, that we realized how sick the youngest really was. Altitude hit harder on Christmas Day than any other and the poor child couldn’t even keep down his lunch. He was finally warm and dry and he didn’t even get the comfort of a good meal. We had him drink the local remedy for altitude sickness, a tea made from local mint leaves. It became our favorite tea and we much preferred it to the ubiquitous coca tea.

Luckily, the boat was a short walk away, though down a couple hundred steps. We had no more stops for the afternoon, just a long boat ride back to the hotel. He slept like only a sick child can, heavy and in a fog, and I only wished he was small once again so that I could cradle him in my arms and hope to help him feel better. The boat windows were so fogged with all our combined hot breath that we couldn’t see much anyway so we all slept.

Our worst day of the trip was behind us and if this was the worst, we could manage the rest. After all, despite the wet weather and the damp cold in our bones, despite the illness of my son, despite the rocking boat and the depressingly gray sky, we met wonderful people. I would visit Peru again in a heart beat and only partly for the beautiful landscapes. The Peruvian people are the true treasure. I hope they know that.

Three years ago, my family was living in Buenos Aires, Argentina. We took the time to travel and managed to see a good part of Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, and Bolivia. This is one post of many from that time period that originally appeared at Daily Kos. FYI – a diary is the same as a blog post in that forum.