First published on December 23, 2014 • Last updated on September 16, 2025

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Our day at Machu Picchu had finally arrived! Yes, it was raining. Yes, we were very tired from having woke up at 3:30 in the morning. Yes, we were worn out from having hiked 25 miles in four days, but we were very ready to see the Old Peak, Machu Picchu!

If you would like to read about Day 1, Day 2, and Day 3 on the Inca Trail, check out these links:

- Camino del Inca: Hitting the Trail

- Camino del Inca: 5 Steps At A Time

- Camino del Inca: Valley of the Rainbows

The Inca Trail – Day 4 – Machu Picchu

When we had arrived earlier that morning, we came in at the top of the city. Instead of entering Machu Picchu right away, we had to walk down the outside steps to the main park entrance. We were greeted at the bottom by an amusement park atmosphere in miniature – a hotel, stores to buy mementos, a fast-food restaurant, bathrooms, and lots of people using all of them. After a brief break, it was our turn to enter the park. We showed our tickets to the entrance guard, pushed through the turnstile, and entered the gate with all the other tourists arriving from Agua Calientes.

It actually wasn’t too busy. A landslide had prevented the first morning trains from arriving and though the tracks had been cleared, passenger service hadn’t yet caught up. We dropped off our backpacks, kept our rain gear, and headed back up the steps we had just walked down a half-hour before! There was actually a practical reason for coming all the way down. Backpacks the size of ours are not allowed in Machu Picchu. The largest you can bring is a 20-liter day-pack and all food is to be kept outside of the park. No picnics allowed!

Our tour of Machu Picchu began at the bottom, just after we re-entered and walked a short way into the site. We spent the first 2 hours with our guide, Fredy, and we learned so much about the ancient Inca, their buildings, their culture, and their influence on modern-day life in Peru. My head still spins with facts and I have a hard time remembering when I learned what but I will do my best to share what I can remember and what I have newly learned since coming home.

The Importance of Water

It seemed appropriate that our first discussion on this rainy day tour in Machu Picchu was about water drainage. It sounds like a boring topic, but the ancient Inca designed their sites to make the best use of water. Their system of agricultural terraces relied on directing water to the right places and also relied on a method to remove excess water so that the soil would not become water-logged and place excess strain on terrace walls.

Research conducted by Kenneth Wright suggests that Machu Picchu was actually designed around its source of water:

Before the city could be built, however, the Inca engineers had to plan how to convey the water from the spring–at an elevation of 2,458 m–to the proposed site on the ridge below. They decided to build a canal 749 m long with a slope of about 3 percent. With the city walls, the water would be made accessible through a series of 16 fountains, the first of which would be reserved for the emperor. Thus the canal design, says Wright, determined the location of the emperor’s residence and the layout of the entire city of Machu Picchu.

This may come as a surprise to some of you as I haven’t explicitly mentioned the royal residence but Machu Picchu was not only a sacred place for visiting pilgrims, it was believed to be an estate for the Inca emperor Pachacuti. His living quarters were centrally located in the city and provide a unique glimpse into the royal Inca lifestyle.

For example, one of the only existing toilets can be found here among his rooms. We asked Fredy about that at an earlier site – it seemed like a natural question while hiking among these ancient homes and suddenly when you have the desire to use the bathroom, it makes you wonder where the ancient Inca went.

Fredy said they didn’t believe in wasting anything so all human body waste went directly to the fields. For many modern-day farmers in the Sacred Valley, this is still the practice. The idea of using nightsoil is abhorrent to many of us but I was surprised to learn that there are ways to use it that are safe and effective.

Failing Water Systems

As we talked about water, we learned that the drainage at Machu Picchu is no longer working as well as it once did. Part of the reason is that neither the homes nor the temples have their original thatched roofs. These roofs would have soaked up a lot of water. Excess water would run off the roofs and be directed away from the buildings. Nowadays, rain falls directly to the ground inside many of these buildings. The damage can be clearly seen as the ancient stone walls have begun to give way to sinking soil. The additional stress of thousands of daily visitors isn’t helping. UNESCO and the Peruvian Government are still debating the best ways to preserve this World Heritage Site.

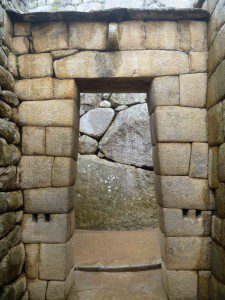

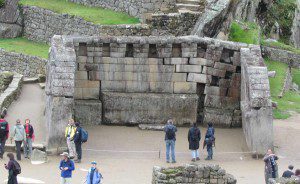

Sacred Doorways

After discussing water, we walked further into the city. We passed a sacred doorway. Fredy had talked at length about the importance of certain doorways at Inca sites, especially doorways to temples and sacred places like royal residences. We had seen some that were double doorways, with two layers of stone offset from one another. All were dry stone laid without mortar and most in the classic style, with polished stones. This doorway at Machu Picchu would have been well secure; it had double holes in the walls on either side and a lintel overhead, possibly for attaching poles and rope to secure a door across the opening.

Temple of the Condor

Temple of the Condor

The next part of our tour took us to the Temple of the Condor. I need to explain the importance of the Condor in Andean Culture, not just to the ancient Inca but to many different people in the past and the present. The explanation begins with the Andean Cross or Chakana. Its shape symbolizes three levels of existence:

The three levels of existence are Hana Pacha (the upper world inhabited by the superior gods), Kay Pacha, (the world of our everyday existence) and Ucu or Urin Pacha (the underworld inhabited by spirits of the dead, the ancestors, their overlords and various deities having close contact to the Earth plane).

Each level of existence corresponds with an animal; the underworld, the Snake; the current world, the Puma; and the upper world, the Condor.

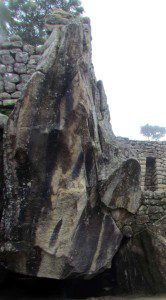

The Temple of the Condor at Machu Picchu is an amazing structure that incorporates the mountain itself:

The Temple of the Condor in Machu Picchu is a breathtaking example of Inca stonemasonry. A natural rock formation began to take shape millions of years ago and the Inca skillfully shaped the rock into the outspread wings of a condor in flight.

On the floor of the temple is a rock carved in the shape of the condor’s head and neck feathers, completing the figure of a three-dimensional bird.

The stylized condor on the ground included a small crevice where liquid could pool. Historians speculate that the small pool was designed to hold blood, partly because its location is the same as the red around the neck of a condor. Fredy discussed the possibility that llamas were sacrificed in this location, a sacrifice meant to honor the mummies that would have been stored in the trapezoidal niches at the upper level just behind the Temple of the Sun.

The ancient Inca believed in preserving their royalty for all time but, unlike the ancient Egyptians, they didn’t place them in tombs. It is well known that they were brought out during important times of the year. The ancient Inca felt that their ancestors helped make important decisions for the community and that their inclusion was necessary:

A curious… practice of the Incas during the time of important festivals and the like was to disturb the dead from their places of rest, dress them up in the finest garments available and, for example, parade them to the Temple of the Sun. The dead also sat in on important meetings and functions, but in all cases were treated with the utmost respect. http://henry-ramsey.suite101.com/inca-burial-etiquette-a8216#ixzz1nWWF0FAb

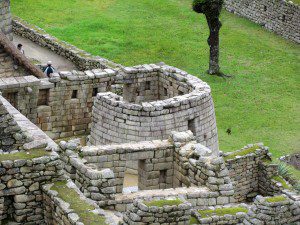

The Temple of the Sun

The Temple of the Sun, which almost appears to sit on top of the Temple of the Condor, has one of the few curved walls I had seen at any Inca site. This Temple holds a special connection with the Sun Gate that we had walked through earlier in the morning. On the day of the Summer Solstice, December 21st in the Southern Hemisphere, the sun’s rays shine through the sun gate directly to the Temple of the Sun and through its window onto a stone altar within its walls.

The skill it would have taken to design both structures is almost unthinkable. We don’t even know what kind of tools the Inca used to build their city; we have even less of an idea of how they were able to measure so precisely that these windows lined up a huge distance apart.

Incan Building Styles

As we walked from location to location within the walls, we learned more about the buildings themselves. Fredy showed us walls of three distinct building styles. One was for common building, like in the residential sector. These stones were not shaped and were often held together with mortar. This style of wall was strong as the Inca still employed many techniques to protect their buildings from earthquakes, such as building the walls at an angle instead of straight up and down and building windows that were trapezoidal rather than rectangular.

However, a lot of the city was not residential; it was either royal or religious in nature and this called for two other styles of building, the Imperial and the Classic. In my online searches, I can find very little information about the two, though it seems like each style developed during a different era. More often people seem to think they are the same and the names are often interchanged. Yet they are clearly different styles and that is best shown by the example of a single wall in Machu Picchu that incorporates both. Although the entire wall has been built with meticulously shaped stones and no mortar, one side has been polished flat. If my memory serves, that is Imperial and the other, more blocky look is Classic.

We also learned that multiple-sided stones were important in themselves and Fredy showed us the stone with the most sides in all of Machu Picchu; it was a type of dodecahedron, a 12-sided polygon. We also saw the smallest stone used during construction, only a centimeter or so in size.

Machu Picchu Was A Work In Progress

Fredy also pointed out unfinished stones in the walls. Machu Picchu was still being constructed when it was abandoned in the mid-1500s. There are several theories but the most prominent seems to be that though the Spanish never found this location, their arrival in the New World sent smallpox into the outlying regions and killed a large part number of native peoples, including the residents of Machu Picchu. This also provides a reason why the city would have been abandoned unfinished.

Each unfinished wall or niche offers more clues as to how the Inca worked stone. Some of the walls have stones with large protrusions on them that presumably would have been polished out when construction was finished. The bumps give a huge clue as to how the stones might have been moved into place as they were large enough for a person to have used their hands. Sometimes even the niches were unfinished. Rather than move a perfectly shaped stone into place for a niche, it seems unfinished stones were used and the interior shape of the niche was polished into place in situ.

Each unfinished wall or niche offers more clues as to how the Inca worked stone. Some of the walls have stones with large protrusions on them that presumably would have been polished out when construction was finished. The bumps give a huge clue as to how the stones might have been moved into place as they were large enough for a person to have used their hands. Sometimes even the niches were unfinished. Rather than move a perfectly shaped stone into place for a niche, it seems unfinished stones were used and the interior shape of the niche was polished into place in situ.

The Reconstruction of Machu Picchu

Later in the day when we were without our guide, we saw other walls with chalked numbers and symbols. Much of Machu Picchu has been reconstructed and we wondered if these walls were waiting to be taken apart and put back together again or if that had already happened. It’s always intriguing to see the work that goes on at a site like this and it would have been interesting to talk with an archaeologist about their work in the area.

The Garden At Machu Picchu

While we were taking close looks at the stonework, we were also seeing wide vistas that included the buildings, the green lawns, and the mountains that surrounded us. In the center of the site there is a lone tree. It doesn’t look very old and I wondered what other kinds of trees might have grown here. Little did I know that one of our next stops would be the garden. What a joy! Although it was small, it provided a small oasis of colorful flowers and shapely leaves. In a space that is so full of stone, the garden was relaxing to the eyes.

It was full of trees and vines, flowering plants, and fruit. We saw the famous Wiñay Wayna orchid, wild begonias, gently draping fuchsias, and the hallucinogenic datura flower, all native plants that we had seen on the trail. We also saw some plants we didn’t recognize including a strange purple stalk covered in what might have been purple corn but didn’t look like any kind of corn plant I had ever seen. The profusion of color was a reminder of something Fredy had told us the day before, that the terraces of Machu Picchu held flowers in great profusion and that the view of the city from a distance would have been very different from the view we had seen today. Instead of huge swathes of green in the terraces, we would have seen garden beds dotted with reds and pinks of lush flowers and the brilliant white bells of the datura. Add to that the gold-covered temples and Machu Picchu would have been a splendor to see.

The soil used to grow all these plants did not originate here in the mountains. Fredy told us that scientists have studied the earth in the terraces and that they hold dirt from different places in the Inca Empire, some from as far away as Ecuador and Lima, Peru. Part of the explanation is that pilgrims were asked to pay for entrance to the city with soil from their own land. Whether this was part penance, like leaving a rock or part of the pilgrimage itself, we don’t know. But it adds to the proof that Machu Picchu saw a wide variety of people from all over the Inca Empire.

Perhaps the most surprising sight in this little garden was a tiny little hummingbird that perched on a branch only a few feet from the ground. We watched his little green and white body launch itself, flit quickly to a flower, and then back again, multiple times. When he came back to rest, he always fluffed himself up. I went back later in the day hoping to catch another glimpse of him or a friend but no such luck.

Machu Picchu’s Quarry

After the gardens, we visited the most important site of Machu Picchu… no, it wasn’t important religiously but without this site, there would not have been a city. It was the quarry. All of the rock that built this marvelous place came from the very mountain on which it was built. From this side of the city, we could look down into the opposite valley and see the terraces drop away at a tremendous rate. The clouds were still building, closing us in, fading away, and then coming back again. But the rain had stopped and it began to feel like we would have a couple of hours of clear weather.

Can you remember what the number seven might signify?

We saw another temple with 7 niches in its main wall. I connected it to the temple at Wiñyawayna with the seven windows, the one Fredy called the Temple of the Rainbow. The one at Machu Picchu was called the Main Temple and no mention was made of rainbows. It was an interesting building because it only had three walls and archaeologists wonder if it was still under construction. In recent years, the main wall of the temple has been sinking and you can see clearly that the wall is in danger of collapsing. This was another structure that looks as if it would have had a thatched roof. The corners of the building have stone protrusions that are used to lash down the roofs of the residential homes. Perhaps a roof over this structure could better protect it.

Intihuatuana Stone

After visiting the Main Temple, we walked up to the next level to see the famous Intihuatana stone. The name of this carved piece of granite means the Hitching Post to the Sun and was likely used to track the sun’s path in the sky:

The Inca believed the stone held the sun in its place along its annual path in the sky. The stone is situated at 13°9’48” S. At midday on November 11 and January 30 the sun stands almost above the pillar, casting no shadow at all. On June 21 the stone is casting the longest shadow on his southern side and on December 21 a much shorter one on his northern side.

The stone is supposed to hold great power and can supposedly transfer its strength to the people who touch it. However, touching it is no longer allowed. According to Fredy, it wouldn’t matter anyway. Years ago, the National Park allowed a television crew to come to this location and film a commercial for the locally brewed Cusqueña beer. One of the tall lights was poorly mounted and it fell, landing on the Intihuatana with such force that it broke a portion of the stone. Since that time, it is rumored that the stone no longer holds the power it once did.

Nevertheless, the stone is a marvel of engineering and science. Each of its many angles seems to correspond to an astrological occurrence and some researchers believe that it is an astronomic clock, measuring time on a yearly scale.

From its high location at Machu Picchu, the site of the Intihuatana looks out over a large open area between the religious and the residential sectors of the city. The acoustics are perfect; a priest could speak from this height and his voice would project into the open space, making it an ideal location for religious ceremonies.

Machu Picchu’s Residential Center

After our explorations of the religious sector, we headed to the residential sector. According to National Geographic, it is thought that only about 500-750 people lived here at any given time, a small city for the Inca. However, the population was most likely very diverse:

One thing is certain, says Bauer, archaeological evidence makes it clear that the Inca weren’t the only people to live at Machu Picchu. The evidence shows, for instance, varying kinds of head modeling, a practice associated with peoples from coastal regions as well as in some areas of the highlands. Additionally, ceramics crafted by a variety of peoples, even some from as far as Lake Titicaca, have been found at the site.

“All this suggests that many of the people who lived and died at Machu Picchu may have been from different areas of the empire,” Bauer says.

I think one of the reasons that Machu Picchu appeals to us is that it has energy emanating from the ancient ruins enhanced by an ancient aura that comes from the mountains themselves. There are very few places to stand in Machu Picchu where you cannot see the high mountain peaks surrounding you. They are everywhere and all-encompassing. I felt like I was standing not in the heart of a city but in the heart of the mountains.

As I looked around me and marveled at the wonders of nature while standing within a wonder of man, I remembered something Fredy told us, that the Inca believed as long as snow existed on the mountain peaks, life would exist on earth. Without the snow from these mountains, life for the Andean people would be unimaginable. Water is the true lifeblood of all humans and we are quickly running out of it. Unless we begin to find ways to mitigate the rapidly changing climate, the mountains will not be snow-capped year-round. I’m not ready to learn if the ancient Inca were right.

It seems that the Inca did not want to forget that they were living on a mountain. The residential sector of Machu Picchu is built into some very steep mountainside. As we walked the narrow paths it sometimes seemed as if the path was just going to drop off into oblivion.

|

|

Our tour ended among the ancient homes and Fredy left us to ourselves. Our plan was to meet him later in the day for lunch down in the town of Agua Calientes. Yes, our day had started so early that two diaries will only bring us to just after 12 noon. Even as I write this, I can’t imagine how we saw so much, and learned so much, in such a short amount of time. It is as if we worked some kind of magic that allowed time to move slowly and let us see and appreciate everything all the more.

My family tackled our time without a guide like we often do, without much of a plan. We only knew that we wanted to head back to the top, to the guard shack, and admire the overall view of Machu Picchu once again. How we got there, which path to take, was much less important because everything in Machu Picchu is worth seeing!

Fellow Tourists in Machu Picchu

Many of the pictures above come from our alone time… we were able to pause and take note, to better appreciate the site itself, the second time through. More people were arriving but the site is so large that the numbers were not overwhelming. I hope that the Peruvian government keeps the entrance numbers close to the same and will not allow thousands more a day.

Most of the visitors were foreigners like ourselves but I occasionally overheard Peruvian tourists talking amongst themselves. Their entrance fee is free yet few Peruvians travel to see this place. The cost of travel alone is expensive, especially in a country with a stark difference between the haves and the have nots.

We did see a large group of local children and their mothers, dressed in the bright pinks, reds, and oranges traditional to the outlying villages. Many of the mothers were carrying babies and toddlers in their carry sacks on their backs and everyone wore hats. The young, unmarried girls had fresh flowers adorning their hats. Some of the group happened to share our lunch spot later in the day and Fredy told us that a large company had paid for them to have this field trip, to see a part of their heritage for themselves.

I wish that every Peruvian could afford to spend some time at Machu Picchu.

Three years ago, my family was living in Buenos Aires, Argentina. We took the time to travel and managed to see a good part of Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, and Bolivia. This is one post of many from that time period that originally appeared at Daily Kos. FYI – a diary is the same as a blog post in that forum.