First published on September 28, 2023 • Last updated on October 5, 2023

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

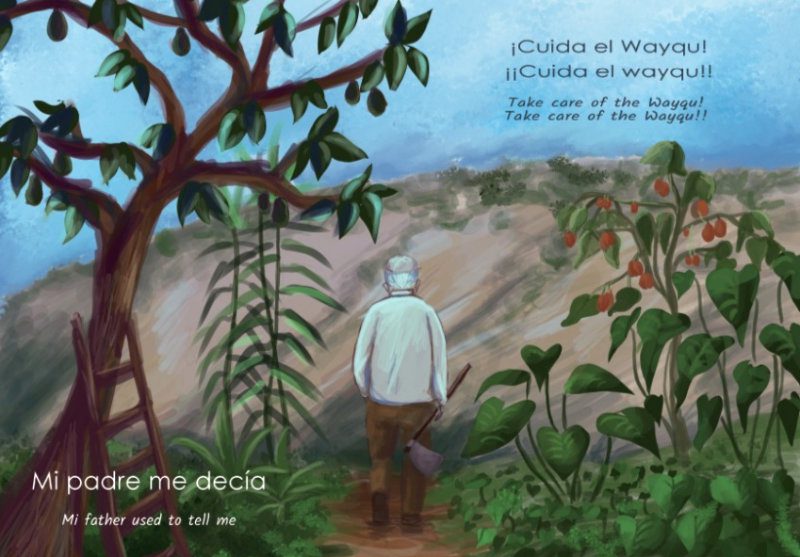

“Cuida el wayqu, mi padre me decía….”

“Protect the ravine, my father said to me…”

With those words, Rolando Luna begins to recite an ode to his father’s incredible work rehabilitating the polluted ravine that runs through the back garden of the family’s property in Pomasqui, a suburban town on the outskirts of Quito, Ecuador. He shares this poem at the end of our tour of PomasQuinde, a dry garden paradise full of birds.

In the beginning…

However, the words he shares are not a farewell. They are an invitation to a new beginning. Rolando invites everyone who visits to care for the wayqu, as his father did so many years ago.

When I first heard about PomasQuinde, it was through the Spanish-language radio program of my friend Jacqueline Granda, Esto Sí Es Ecuador. I was intrigued, intent on learning more on my next trip. So last March, while headed to Refugio Paz de Las Aves, my friend Miguel and I stopped for a visit. We spent a wonderful hour or so touring the grounds, hearing Rolando’s story, and observing the birds. Oh, what a lovely selection of birds to see! But more on them in a moment.

Rolando inherited this property from his father, Luis Alonso Luna. After his father’s passing, Rolando felt called to follow his incredible example in preserving a piece of land that many Ecuadorians see as a place to dump garbage.

You see, the quebradas of Quito are narrow canyons and ravines that cut down the Pichincha Volcano, allowing water to run riot during the rainy season, even in the driest parts of the region like Pomasqui. These rains serve to wash away the garbage and sewage that collects from homes that use it for their trash. This is, and has been, a common practice for generations.

It is only recently that people have begun to understand that these quebradas provide essential habitat for native plants and wildlife. They deserve protection.

A Visionary Arrives in Pomasqui

Luis Alonso Luna was a visionary. In 1992, when he moved to Pomasqui for its dry climate, a recommendation from his doctor who said the constant humidity of nearby Nanegalito was not good for his health, he saw promise in his new garden. This despite the smell of sewage and presence of only a single avocado tree.

According to Rolando, his father cleared out the garbage and planted trees, bushes, herbs, and flowers. Some native, some medicinal, all important to creating a habitat that was liveable for both native species and the family who called it home. This was not the work of a single year. It became a passion that took decades of dedication. His neighbors thought him crazy for undertaking such thankless work.

Some of plants he added to the garden included caballo chupa, a relative of horsetail. This plant is known for its faint scent of oranges and helped mask the smell of sewage. He also added guanto, an evergreen shrub of the Brumansia family with huge, bell-like flowers best known for its illicit use, scopamine. But a more benign use is to take the leaves and place them in a child’s pillow to help them sleep through the night. No Andean home is complete without a guanto guarding its entry. He also planted matico, a tropical evergreen named for a Spanish soldier who learned from native South Americans that it would disinfect wounds.

As the garden grew year after year, a subtle change took place. The birds returned to the quebrada. They came to sip from the slender yellow flowers of the tabaquillo, to find protection from the harsh Equatorial sun in the shade of the avocado tree, and to hunt insects in the compost pile. Planting trees returned the natural humidity to the quebrada, providing respite in a microhabitat that sits in the rain shadow of the tall volcano. Don Luis Alonso literally created an oasis in the desert.

This is the Wayqu that Rolando inherited, a lush garden exuberant with lively birds.

Our Tour of Pomasquinde

When Miguel and I arrived at PomasQuinde, we new exactly which house to go to. The facade is painted in a stunning mural of an older woman smelling a bright red flower while looking at a brilliant green and blue hummingbird frozen in flight before her eyes. If we were in doubt, the words PomasQuinde are painted next to the door where we merely needed to ring the bell. Rolando opened the gates so that we could park inside. We later learned that this beautiful mural was donated by @dereo.graffiti, a well-known artist in Quito.

We walked directly past the house onto a small patio in the back with views directly into the canopy of a huge avocado tree. Hanging from the branches is a complex set up of bird feeders. Rolando explained that the design is to prevent feral cats in the neighborhood from hunting the birds that come to eat the corn and other grains he provides.

In a few short minutes, I observed Shiny Cowbirds, Blue and Gray Tanagers, Golden Grosbeaks, and lovely Saffron Finches. According to eBird, these are only a few of the 32 species identified in this urban backyard garden.

We stood here talking about the history of the garden as we continued to watch the birds. A Giant Hummingbird made a regular appearance at one of the sugar feeders. Several Sparkling Violetear hummingbirds flitted through the hanging taxo fruits. And I managed to snap a very poor photo of a Green-tailed Trainbearer Hummingbird as it dashed past me towards a feeder in the distance.

This is a place where I would love to sit for hours, plotting out how to get the best shots of the birds by noting their consistent behavior.

Entering the WayQu

Then Rolando asked if we would like to take a walk. We entered a small path that dropped down, passing under the avocado tree once again. Small ground doves were eating the corn on the hillside, posing as we walked by. We also saw a huge rooster that Rolando jokingly referred to as the PomasQuinde mascot. One more turn and we reached the base of the huge avocado tree.

This tree has survived at least 65 years, many of those spent without a caretaker or a steward of the land. Today, the family calls this tree Guerrero, or Warrior, as a tribute to its fight for survival.

This is also the sacred entrance to the Wayqu, a place where Rolando’s father would always pause and ask permission to enter. Of course, we did the same, as does every visitor to PomasQuinde, grazing Guerrero with out fingertips as we quietly walked by.

In this place, the sounds of the city recede into the background and the cool air rises from below. If I lived here, this would be the spot where I would sit and meditate, using the Wayqu to clear my mind and cleanse my spirit.

Rolando proudly showed us his father’s gift to us all. He pointed out the plants mentioned above and many more, like nogal (walnut), capuli (wild cherry), higo (fig), and arrayan (a type of myrtle tree that bears an edible fruit). Its incredible how he and his father before him have managed to grow such a variety of plants in a relatively small and arid plot of land.

At the base of their property, he explained how, in this dry climate, they recycle all of the water from the house. Only sewage goes into the quebrada, a practice that continues because the city does not provide any other way to remove it.

However, since our visit, Tucaya Travels has funded a project to prevent sewage from backing up on the property, an important improvement needed to continue providing tours at PomasQuinde.

We harvested tomate de arbol from the fruiting trees below and admired the resilient garden, looking up from the quebrada towards the house, hidden behind layers of foliage.

And this is when we heard the ode Rolando wrote for his father. The emotion with which he recited this poem permeated the Wayqu and directly entered my heart. Even as I sit to write this article, my eyes fill with tears and gratitude for this incredible opportunity to learn and share in the history and modern day story of PomasQuinde. I am truly humbled by Rolando’s accomplishments.

As we walked back up the path, both Miguel and I couldn’t resist one last chance to hug Guerrero. It would serve to replace the hug that I would prefer to give to Don Luis Alonso, to thank him for his hard work and dedication to protecting a habitat no one else thought worth their time.

Visiting Pomasquinde

PomasQuinde is a truly a labor of love. Rolando works tirelessly to protect and feed the birds with the consistent support of his loving family, including siblings and cousins.

The amount of money that comes from entrance fees sometimes barely covers the cost of grain. Of course, as word gets out about this very special place, that will hopefully start to change.

We highly recommend making a reservation to gaurantee that Rolando is at home. Rolando can be contacted via Facebook, Instagram, or WhatsApp (+593 98 626 0257).

If you take the time to visit, be sure to take a donation. The entrance fee is small for an international visitor. Please consider leaving more as a way of thanking Don Luis Alonso and Rolando for their incredible work.