First published on September 4, 2019 • Last updated on September 6, 2019

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

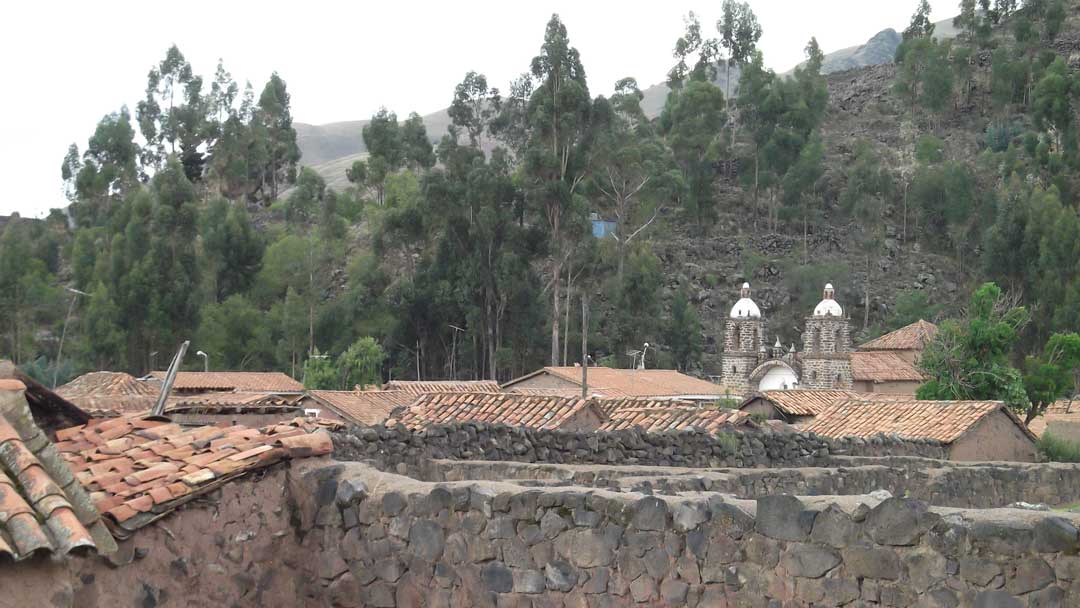

Puddled dirt streets, patchy orange-tiled roofed, adobe brick homes on one side, views of fields dotted with llamas on the other, lead me to an alley. Halfway up, at double wooden doors, Lydia welcomes us to Raqchi and her home, our accommodation for the night.

Our Guesthouse in Raqchi

I step into a long narrow room, bare except for pottery for sale on shelves at one end, a wooden dining table in the middle and a computer, looking very out of place, at the far end. A door opposite leads to a compacted-dirt courtyard, rocks embedded here and there. Lydia shows me to a bedroom off the courtyard. Beds covered in heavy blankets look cozy under the bamboo ceiling. A hot shower and toilet are a welcome sight in a separate small, orangish, mud brick building.

Given that its 2 pm, we’re immediately served lunch from a tiny kitchen which consists of a stainless steel sink between lopsided tile benches. Pots sit over holes in the mudbrick oven/stove. Flames flicker below in a narrow opening. The oven is a larger, blackened opening. A tomato, cheese, and onion salad come before a soup with potato and quinoa, then alpaca meat with two more potatoes. Peru is the home of potato, with somewhere in the vicinity of 4000 varieties. Along with corn, quinoa, and wheat, they’re grown here in Raqchi.

Incan Ruins in Raqchi

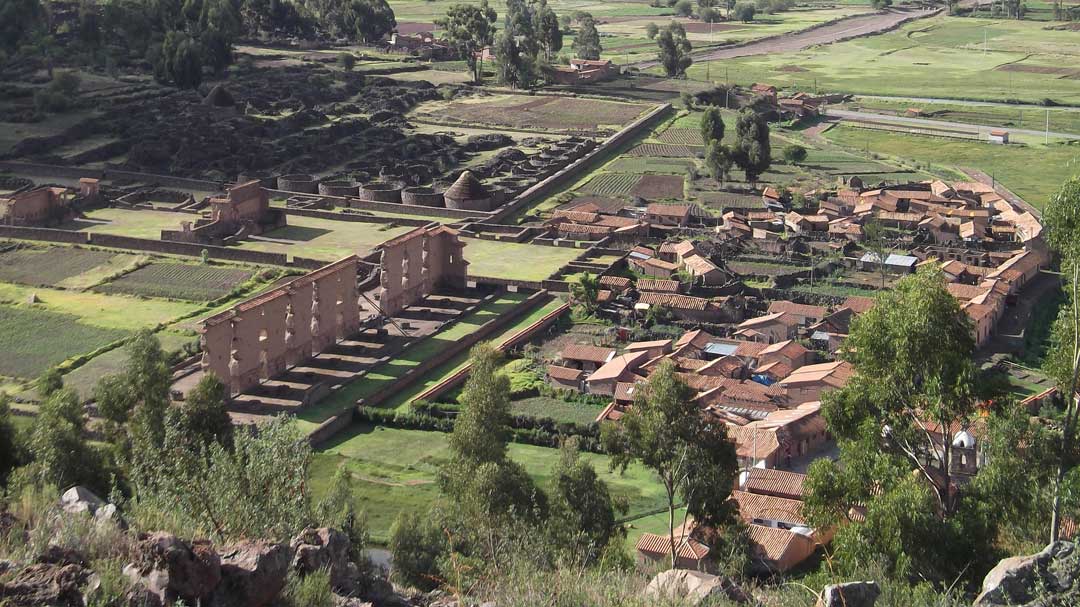

Surrounded by crop-planted fields, this rural village of around 300 inhabitants borders Incan ruins. I walk the meal off exploring them.

According to legend, the Inca felt threatened after the nearby Kinsacha Volcano erupted. It prompted them to build a temple to honor Wiracocha, the creator of heaven and earth. Covering an area of hundreds of hectares, the temple was built during the 15th Century, about the same time the Inca were adding territory in Ecuador. The edifice was almost completely destroyed by Spanish colonists in the 16th Century.

The Temple of Wiracocha, apparently around 60 feet high, 80 feet wide and 300 feet long, is thought to be the tallest Inca structure ever built. Only walls remain, consisting of a 13 foot high stone base, topped by adobe. A corridor aligns with the December solstice’s rising sun, summer in Peru and an important date to the Inca. On this day, they gave thanks for crops.

Crops were stored in thatched, conical-roofed storehouses, called qullqas. Two tiny windows give ventilation and a narrow door provides access to these circular, 26 feet in diameter, granaries. With slightly sloping walls, built to withstand earthquakes, 156 qullqas remain, several restored to their original state. The Inca traded stored produce. They also used it to feed travelers passing through on the 14,300-mile Qhapac Ñan, the main road that connected important centers throughout the Andes.

Local Pottery

The area is famous for its ceramics and we attend a pottery demonstration. On wheels turned by hand, local women shape dishes. They dig the red clay from surrounding hillsides. They grind the clay with a semicircle of metal or wood, rolling the tool back and forth until the clay is like dust. Water is then added to make the clay pliable. The woman fashion bowls, mugs, plates, ornaments, jugs, and chess sets – where Inca versus Spanish conquistadors – some plain, others decorated with colorful Inca designs. The jugs are intriguing. Liquid is poured into a hole at the base but when upright, it stays put and is poured out like a normal vessel. Beyond me!

Rural Raqchi

Wandering back to our home, we pass one and two-story adobe houses, some earth-plastered a pinkish-orange, others just grey mud bricks. A pig on two legs peers over the top of a high rock wall. In the main plaza, where grass grows between cobbles, stands Capilla San Miguel de Raqchi, a stone chapel with two bell towers built in 1900. I think it’s the only building in the village not constructed of adobe.

Evening in Raqchi

Dinner comes with more potatoes. I feel ungrateful leaving them, given my humble surroundings, but I can’t eat another one.

Evening sees us dressed in traditional outfits. I wear a thick full skirt which reaches mid-shin, a heavy and heavily-embroidered jacket, a large black wool hat resembling a plate and llama wool boa. The men wear knitted, brightly colored woolen hats and colorfully fringed cream ponchos with Inca designs in stripes. By torchlight (there’s no street lighting) we follow Lydia’s husband through the near-silent village, stumbling on uneven dirt tracks, to a courtyard within another home.

Others from my tour group arrive. They are also staying in the community. We sit in a semicircle. One of our hosts gives us coca leaves for each hand: three for Pachamama (mother earth), three for Apus (the spirits of the mountains). One by one, we proceed to kneel before two vases on the ground. One contains pink flowers, the other red. Blowing the coca leaves, I’m meant to wish or pray before placing the leaves into the vases. I forget. When everyone finishes, the vases are brought to each of us. We each blow three times into each one. They are tapped on our heads. The solemn but bewildering ceremony ends with the coca leaves buried, a gift to Pachamama.

I’m thankful for the heavy clothing I wear, it’s around 9°C. (48°F). This is summer at 3500 meters (11,400 feet) in elevation! An open fire burns in the courtyard and our homestay families encourage us to dance to music they play.

We leave the next morning, each gifted a chakana – an Inca cross. It’s a fitting gift from this village steeped in tradition and surrounded by Inca history.

Loved your story about your homestay in raqchi. Would it be possible to send information and contacts on how to stay a few days in Raqchi. I speak Spanish, I am a potter living in Virginia. and enjoy quietly taking in the culture with locals. I am visiting soon and this seems like a place I would love to support and learn from. Thank you!

I reached out and have a name and contact information coming!