First published on December 5, 2014 • Last updated on February 7, 2018

This page may contain affiliate links; if you purchase through them,

we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you.

Dawn comes early in the Andean mountains of Peru and we woke up before the sun. I could hear the porters in the kitchen tent heating water and preparing breakfast. I took it as a sign to start pulling my belongings together. As one of the slowest hikers on the trip, I refused to be the last one to be ready to hit the trail and started to stuff my sleeping bag before the porter arrived with my coca tea.

Inca Trail, Day 2

Today would be the most difficult day of our 4-day trek on the Inca Trail. We were facing a climb of more than 2900 feet from our camp to the highest pass on the trail. Immediately after the pass, we would descend 2,300 feet to arrive in the largest camp, Paqaymayu. Most hikers would stop there for the night – an average 6-8 hours of hiking for the majority. However, our own group would push on as our campsite was 2 hours further along the trail. It meant hiking over a second pass and ascending another 1,500 feet before dropping down again.

Okay, I am tired just from reading that. Take a deep breathe and come enjoy my day because, as hard as it was and as much as I am going to make you feel that difficulty with me, I had high points that I wouldn’t exchange for the world.

Breakfast was a welcome event – warm food is a great way to start a hiking day and our cook made the best drinkable oatmeal I have ever tasted. I poured it into my cup and enjoyed its creamy texture and the hints of cinnamon and nutmeg. I will have to rethink how I make oatmeal at home! My boys and husband chowed down on pancakes with dulce de leche and toast with jam, washing it all down with coffee and hot chocolate. I doubled up on my coca tea with hopes that it would help me better handle my problems hiking in altitude.

My pack and that of my youngest son had been given to two of our porters. We had decided the extra cost was well worth it. At the time, I had thought two new porters were hired from locals in the area but I found out later that our packs were added to the heavy loads that were already being carried by our own. By law, porters are not to carry more than 20 kilos. It sounds as if many people turn a blind eye and though the Porter’s Union has fought for these laws to be passed, they are not always followed. Organizations attempting to help the porters ask that tourists still come to the region and to do their best to use ethically and morally responsible companies, yet there is no up-to-date list of these companies. It was only after our trip that I began to research more about organizations to help the porters and found the websites Porters of the Inca Trail and The International Porter Protection Group. The questions that haunted me while walking the streets of Cusco took on a new life on the Inca Trail and I began to wonder what we would think of tourism in the Grand Canyon of Arizona or the Chilkoot Trail of Alaska if it meant using Native American labor to haul packs for visiting tourists. It was a topic that I would think of more as our trek progressed.

I was left to carry a small shoulder bag with water, light snacks, and my rain poncho. My eldest son chose to hike with his younger brother – he carried his water and his rain poncho for him as well as carrying his own gear. Honestly, he was one step away from wanting to help the porters and helping his brother was the next best thing. We also learned that we weren’t the only ones giving up our packs for the day. I guess yesterday had been harder on other hikers than I had thought and many of them were paying porters to help them with the ascent.

Camera in hand, I started up the trail ahead of our group. I was quickly passed but I didn’t let it bother me. Instead I vowed to enjoy the hike as much as I possibly could while still moving forward. I knew that starting too fast would only come back to bite me later in the day, so my first steps through the forest canopy were unrushed and consistent. When I stopped to catch my breath, I looked around and enjoyed the lush plants, listened to the morning song of birds, and caught the occasional glimpse of mountain vistas when the forest canopy allowed.

I shared the trail with my husband. I had tried to convince him to stick with our boys (I was worried about the little guy, of course) but he stuck with me instead. I think he was worried but he never said so. At this point in the day, I was confident that I would finish and I knew that our guide was keeping an eye on me as well. Fredy managed to catch up and check on me in between his visits with people he knew on the trail and his own explorations. He told me later that he sometimes enjoys hanging back and taking the time to discover new plants or to see a different bird. I know what he means because that is how I like to hike most of the time!

Sometimes, hikers from other groups would chat as they went by, even slowing down for a few minutes to hold a conversation. It seemed that all tour groups were allowing each hiker to tackle this trail at his or her own speed. Almost everyone spoke English though we did meet a French woman who spoke neither English nor Spanish and her guide wondered if she understood very much at all – he spoke no French. But English definitely carried the day, unless you wanted to speak with porters and then Spanish had to do. They spoke among themselves and to most of the guides in Quechua and I loved to listen and see if I could catch any words.

We also shared the trail with some kick-butt llamas. There is nothing more surprising than to turn around and find that the footfalls behind you come from quadrupeds, not a group of fellow hikers. My husband learned to stay out of the way as llamas have a habit of baring their teeth at anyone who is slow to understand that they own the trail. We also jumped out of the way when we heard porters on the move. They hustled quickly. They were easier to hear during the rain as they wore heavy tarps for rain protection that flowed behind them like super-hero capes. The rustle of the thick plastic could be more easily heard than their soft footsteps on the ground.

The trail was damp with last night’s rain and the trees still dripped with mist from the clouds that hung in between the mountains. The trees were gorgeous in the morning light. With all of the water available in the cloud forest, these trees grew prolifically but none of them could have been used to build a house or a fort. The trunks were slender and curved, all of them slanted and twisted towards the sunlight. Fredy told me that the Spaniards were frustrated by the lack of wood to build and they brought in the Eucalyptus in response. Many Peruvians are struggling to keep the invasive species at bay, but others insist on keeping it for its utility.

|

|

|

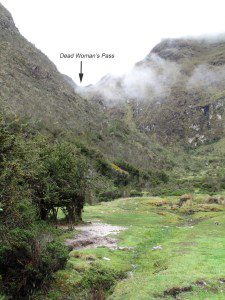

By about mid-morning, we made it to our first meeting point at Llulluchampa. This gorgeous spot provided a break just before we were to tackle the steepest part of the trail. The valley opened up and llamas grazed nearby. The last of the vendors were here as well, selling water and candy for those who didn’t pack enough for the trail. My group was waiting for me, sons included. They were well rested and chomping at the bit to head up the mountain. Clouds were building and it looked like it might rain again. It would be good to be up and over the mountain before it started pelting down. I had enough time to use the bathroom and take some photos both up and down the valley before climbing the the White Man Killer Steps. Yes, that is how they are affectionately known by some of the guides.

One of my sons kindly pointed out the top of the pass from where we were standing. I think he was trying to be helpful. In Yosemite terms, it didn’t look so bad. In Andean terms, I decided that I could not make the pass my goal. That may sound kind of funny, like I was giving up before I had already started, but that height looked unattainable from where I was standing. I had to find a way to do this. I knew that I could hike the next five steps. And then I could make the decision to hike the next five. And then five more after that. And that is exactly what I did. I decided on five steps because that was about the amount I could walk before a wave of nausea attacked both stomach and head. Then I would stop, take some deep breaths while looking over the side of the trail into the valley or leaning against the rocks and focusing on details in the flora and fauna.

This was literally the hardest hike of my life and it wasn’t because the trail was technically difficult. It was steep but there were steps to walk on. I wasn’t rock hopping, rock scrambling, or even partially rock climbing, all of which I have managed in the past. I was literally lifting one foot and putting in front of the other onto the next step. This trail was slowly but surely killing me by sapping my oxygen.

A few times, I found myself looking up to see how far I had come. I immediately regretted each time I did so. I felt a wave of apathy come over me as I increasingly realized that it was taking me forever to move even a few feet forward. I wondered if I should just sit down and stop and let Fredy find me and tell me it was time to go back. But always, my husband was just a step behind and I just couldn’t turn and tell him I couldn’t do it. I almost did but his quiet, focused support was enough to stop me from speaking those words. My boys were hundreds if not thousands of steps ahead, possibly up at the top waiting for me. So I stopped looking up and stopped thinking of feet climbed and focused once again on those five steps. They became a mantra for me.

Honestly, this part of the trail is almost a blur. I can remember looking down in the valley and seeing the triangular ditches used to drain the old campgrounds at the top of the valley. I can remember a pretty little bird, black head and wings, an orangey-red chest, with white markings on his throat and under his wings. One of the guides told me what he was and I’ve since forgotten and can’t find him in my book. Many people were very kind to me that day and it’s all a blur of faces. I spoke with a man from England who now lives in Las Vegas. It seems that he would pass me by, then he would rest a while somewhere else on the trail, and I would see him passing me again later on. Four or five times at least. Or maybe there were several Brits who lived in Las Vegas passing me that day. In my altitude sickness fog, anything was possible.

Hours later, or maybe it was minutes that just felt like hours, Fredy was telling me that I was almost to the top. Just a few more steps and I would be at Warmiwañuska or Dead Women’s Pass, the highest summit on the Inca Trail. I felt like a woman near death but just that brief moment of knowledge that I had almost made it was enough to send me those last steps, still resting every five, and make it to the saddle.

After Fredy took our picture, I cried from relief that I had made it this far; I cried because I still wanted to throw up and couldn’t; I cried because I still had so far to go and then I stopped thinking. I couldn’t think that far ahead and it was better to shut down my brain and live in the moment, even though the moment was colored by waves of nausea. My husband and I sat at the top and looked back over the mountain and looked down, down, down that trail and I cried again because I just could not believe I had actually made it to the top. Just Llulluchampa looked formidably far and we had come from further away in a single morning.

The difference from one side of the mountain to the other was striking. On one side, we could see very far, even though the clouds were building in the distance. On the other, it was near impossible to see a thing. The clouds had sucked up right next to the mountain and the rain was falling in a consistent, steady manner that mean not only would we get fairly wet but that the trail would be slick and dangerous.

We hiked straight down for a long time, the steps uneven and often so high that I was turning to one side and letting myself down by using the power in a single thigh to lower myself to the next level. Then I would turn around and use my other thigh, because I knew better than to give one side of my body all the work – otherwise there would be hell to pay tomorrow.

We hiked past rushing streams that sometimes crossed the trail and through lupin covered hillsides. The rain just kept coming and my poncho helped only slightly. I had worn three-quarter length pants that day and I was glad because it meant there was less of them to get wet. However, it meant my hiking socks were open to the elements. Light rain wouldn’t have been a problem but heavy rain meant that my socks acted like wicks for an oil lamp and transferred rain from the outside of my boots to the very bottom of my soles.

The good news about hiking downhill is that I didn’t lose my breath. I no longer had to stop every five steps and could hike with a sustained gait. As I started feeling a little better, I gained more confidence and as the trail evened out in some locations, I stretched my legs and picked up speed. I was bound and determined to get to our lunch camp at a decent hour. Unfortunately, the altitude was still affecting my body and my coordination was not as good as I had thought. My firm step on the next wet rock went me flying, face first, hands spread wide to help stop my fall, onto the slippery trail. Later, Fredy told me it was the most spectacular fall he had ever seen. I was lucky – just two lightly grazed palms and a bruised ego. Up and at ’em again, hiking at a reduced pace because my confidence was just shot. I don’t think I could be much more demoralized and get through the day.

Then, miracle of miracles, the rain slowed down and finally came to a stop. The trail was still wet, but we began to dry out a little and the birds began to sing. They helped lift my moral.

|

|

|

And I got lucky. While standing for a few minutes to rest, I took one of the best photos of the whole trip. A hummingbird came out of nowhere and landed on a nearby flower. The flower itself was one of the ugliest I have ever seen and I would never have imagined that it would attract a hummingbird. It looked more dead than alive, a dull colored grey stalk with flower buds that looked like dead artichokes, thorns and all. From each artichoke-like bud came a dark purple-green flower with brilliant yellow stamens. And here was this brilliant blue streak landing on the stalk immediately in front of me. He visited several flowers on the stalk giving me a unique opportunity to take his portrait.

When we finally arrived at our lunch spot, I remember the strangest thing, women walking around in flip flops, short, and t-shirts and with towels wrapped around freshly washed hair. Those lucky women not only got to take showers but would spend the rest of the afternoon resting and recuperating. I, on the other hand, had another two hours to go. I wished that we could be making camp in this very same spot.

Lunch was spent in a cramped tent steaming with dripping rain gear that hung from every available space. I know that I didn’t eat a lot. The memory of eating too much the day before was still very fresh and I needed nothing more than some soup and coca tea. My boys however, were starved and ate everything put before them. They were also very animated – they both had an excellent morning and my youngest was hyped from having hiked so much better than the day before even though the terrain was more difficult. Having him hike without a pack made a huge difference and he had found his confidence once again. He told funny stories and made everyone laugh. People are often amazed that my young men can talk to adults with such ease. Military life has introduced them to many new people and given them the ability to talk with ease, especially when the adults they are talking to are willing to listen. Conversation jumped back and forth from the trail to Holland and the Netherlands to travel in Ecuador and to the differences between our own hotel and the youth hostels of Cusco. There was an easy give and take at lunch that enabled me to enjoy the conversation without participating much in it – you don’t know how strange that is for me, to sit there and not talk. But I don’t remember having much to say.

After lunch, it was back to hiking UP the trail to another pass. But the afternoon hike also included visits to two sets of Incan ruins. The first set were right along the trail. The last set meant a detour of a 1/2 hour and a murderous set of steps to get to them. We already knew that I wouldn’t be seeing the last set. My body was demanding rest and I needed to get to camp.

My youngest son decided that he wanted to hike with me during the afternoon. At first, I didn’t want it – I was afraid that we would hold each other back. Usually, even on the worst of hikes, I always found a way to give him strength to get up the mountain or down the trail or through the scree or across the snow. I was afraid that in my current state of mind, I wouldn’t be able to help him. But I shouldn’t have worried – he wanted to help me.

The trail out of camp was an immediate accent and I was faced with those damned steps once again. I told him I could only handle about 5 at a time and he helped me to take six or seven or eight. He focused not on the steps but on the next wide spot on the path or an interesting flower or a great view and encouraged me to get just that far. He told me later that he wanted to do for me what I had done for him when he was younger. This hike was bringing out the best in both of my young men.

Shortly out of Camp Paqaymayu, we saw the ruins of Runkurakay. My husband and I took the path around and viewed the ruins from below. My boys both went up and into the ruins. There, they listened to Fredy tell them about the small site. It was most likely a Tambo, or a place where the Chaskis would live. Fredy had explained to us how the Incans had built different kinds of communities at different locations on the trail to maximise their efficiency. Agricultural towns were large and fairly far apart from one another but Tambos were built only a few kilometers apart to enable Chaskis to run in between them fairly quickly and without expending too much energy. In this way, the emperor of the Inca Empire could receive fresh fish from the coast all the way to Cusco and a message could travel from Cusco to Quito in a week.

As the afternoon progressed, I realized that I was having increasing difficulty. At one point, I told my husband that I wasn’t thinking straight. I knew enough to know something was wrong but not exactly what it was. I knew that I had to put my foot ahead on the trail but my thought process was so slow that I actually had to stop, think, look, place my foot, look ahead and start the process all over again. Fredy asked how I was doing and when I told him, he asked me some basic questions to make sure I wasn’t suffering from the worst case of altitude sickness. I didn’t have tingling in my fingers or in my lips. He told me that I just need sleep and rest and I could have that once I got to camp. I needed to keep moving. So I did.

As we approached the next pass, the weather cleared and the nearby mountain ranges played peek-a-boo with us. We would watch the clouds dissipate and the mountains would begin to appear and then, like magic, the clouds changed shape, grew thicker and the mountains were gone once again. It was like someone was playing with the remote control and switching in between two channels – mountains and no mountains. I was surprised to see two high mountain lakes, still and calm, reflecting the cloud filled sky. From this height, I felt like I was on top of the world. It is bizarre to feel both extremely unhappy and inspired at the same time. The range of human emotions is truly remarkable.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The day got later and later and camp seemed to get no closer. I was more tired than I had ever been in my life. Later, I learned that this is another symptom of the altitude. When I got home and did a little more research, I learned that I had four of the five symptoms of Acute Mountain Sickness – disorientation, loss of coordination, lassitude, and nausea. Thank goodness I was minus the headache. When Fredy asked me questions, he was trying to ascertain whether I had either HAPE, High Altitude Pulmonary Edema or HACE, High Altitude Cerebral Edema. When he told me what I needed was rest and sleep, he was right. Furthermore, when he told me camp was where I needed to be, he was correct as well. The lower altitude campsite, though 2 hours further down the trail, was actually better for my health, though I didn’t understand that at the time. My body would better recuperate at the lower altitude camp.

When I finally reached the branch in the trail that would take us to the last Inca site, Sayaqmarka, Fredy was waiting for me. He pointed me towards camp and said it was about another hour to go. It was after five in the afternoon and the sun was low. We told my son to kick it in gear and leave us behind. It was bad enough that I might be hiking this trail with a headlamp. I didn’t want him to be hiking that way as well. Fortunately, the trail leveled out somewhat and I picked up speed. We were lucky enough to catch a glimpse of the ruins on the way to camp. They sat on an outcropping opposite the trail, the dark gray stones blending in well with the surrounding jungle. From our brief look, we could see the site was large enough to be some kind of town and obviously served as more than a stopping point for the Chaski. The misty clouds made them look mysterious, as if they were still waiting to be discovered. Maybe they still have secrets to tell.

One heavy footfall after the other and I managed to pull into camp just before dark. My husband had kindly filled my sleeping pad with air and laid out my sleeping bag while I visited the bathroom. After that, I literally went to bed. My body craved sleep, not food or conversation, so I skipped dinner. As I drifted off, I could hear the happy laughter of my campmates and very briefly felt sorry for myself. I’m the kind of person who hates to miss a thing. And then, before I could think any more, I was fast asleep.

We started our day at Camp Yuncachimpa at 10,824 feet and ended our day at Camp Chaquiqocha at 12,033 feet. After all the ups and downs, our day’s hiking gained us a total of 1640 feet in elevation. We had hiked over 15 kilometers or about 9 miles.

In total, from day one, we had gained 3505 feet and hiked a little more than 15 miles.

From this point on, everything would be more downhill than uphill.

Three years ago, my family was living in Buenos Aires, Argentina. We took the time to travel and managed to see a good part of Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, and Bolivia. This is one post of many from that time period that originally appeared at Daily Kos. FYI – a diary is the same as a blog post in that forum.

I think I could help you out with that… just let me find the time to write it!

AJ, you are fortunate: a) to have these memories, and b) be free of HAPE.

I would think, now that you are in Quito, you are acclimated.

As usual, I loved your post! How ’bout one on shopping in the Capital City?